The COVID-19 pandemic brought unprecedented changes to the world, and zoological parks was no exception. With lockdowns came the temporary closure of zoos, offering a rare glimpse into the lives of animals devoid of the usual human visitors. This disruption provided researchers an extraordinary opportunity to study primates in a unique context—one that might reshape our understanding of animal welfare in captivity.

During the pandemic closures, several zoos in the UK observed a mix of behavioral changes in their resident primates, highlighting the complexity of these animals’ interactions with their environment and the humans who frequently populate it. Researchers focused on four primate species: bonobos, chimpanzees, western lowland gorillas housed at Twycross Zoo, and olive baboons at Knowsley Safari.

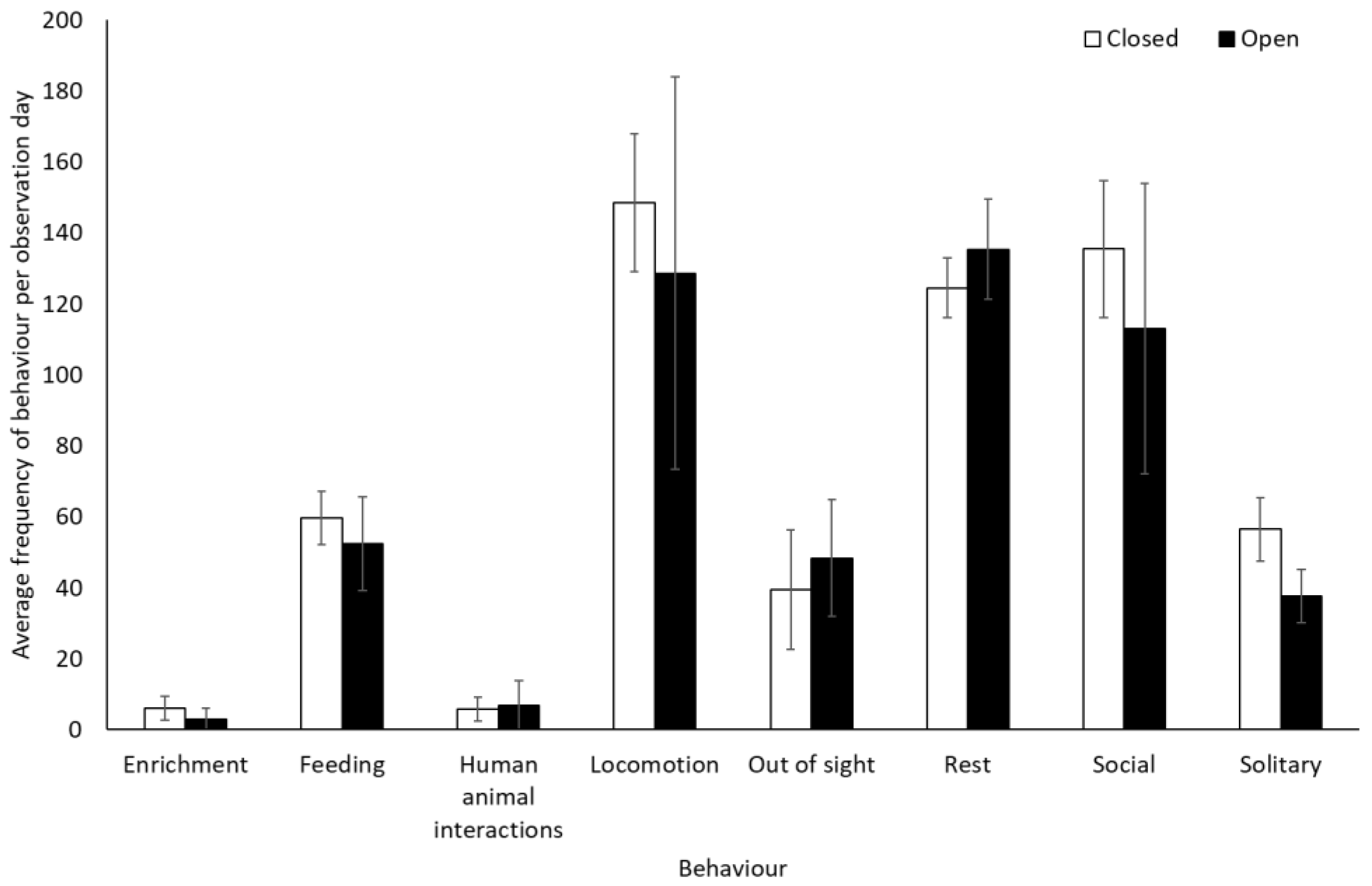

The study employed both behavioral observations and physiological measures to discern the impacts of this sudden solitude. For instance, bonobos and gorillas were noted to spend less time alone when zoos reopened to the public, suggesting that the presence of visitors might reduce their solitude. Gorillas, in particular, appeared to rest less when visitors were around, perhaps indicating that the presence of humans disrupted their usual routines or provided a stimulating influence.

Chimpanzees exhibited an increase in both feeding and interaction with enrichment activities during reopening phases. This spike in activity could suggest that the return of visitors was a form of enrichment itself, though not all primate responses were so easily categorized as positive or negative.

Olive baboons presented a particularly intriguing aspect of the study. These primates showed reduced sexual and dominance behaviors while engaging more with vehicles when the safari park was open. The observations suggested a possible saturation point with visitor interactions, beyond which additional stimuli no longer resulted in increased engagement.

Across the board, physiological measures, specifically faecal glucocorticoid metabolites (FGMs), showed no significant changes between the open and closed periods. This suggests that, despite observable behavioral shifts, the physiological stress levels of these primates did not fluctuate drastically due to the presence or absence of visitors.

From a broader perspective, these findings underscore the adaptive nature of zoo-housed primates when confronted with environmental changes. The variability in responses also highlighted the individual differences among species and even within species, driven by factors such as past experiences and personality traits.

While the opportunity to study primates in this context was unprecedented, the study was not without limitations. The brief nature of the closure and reopening periods, coupled with the heterogeneity of primate responses, suggests that more nuanced studies are necessary to fully understand the intricate relationship between zoo visitors and primate welfare. Future research could also explore the long-term implications of such environmental changes and look into how these temporary closures might inform future zoo management and visitor interaction policies.

Related Posts

Reference

Williams E, Carter A, Rendle J, Fontani S, Walsh ND, Armstrong S, Hickman S, Vaglio S, Ward SJ. The Impact of COVID-19 Zoo Closures on Behavioural and Physiological Parameters of Welfare in Primates. Animals. 2022; 12(13):1622. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12131622