The vast landscapes of Botswana have long been home to the majestic African elephant, a creature often seen as a symbol of strength and resilience. But in 2020, the tranquility of this wilderness was shattered by a mysterious tragedy. Hundreds of elephants were found dead under the African sun, their tusks untouched by poachers, leaving scientists and conservationists scrambling for answers.

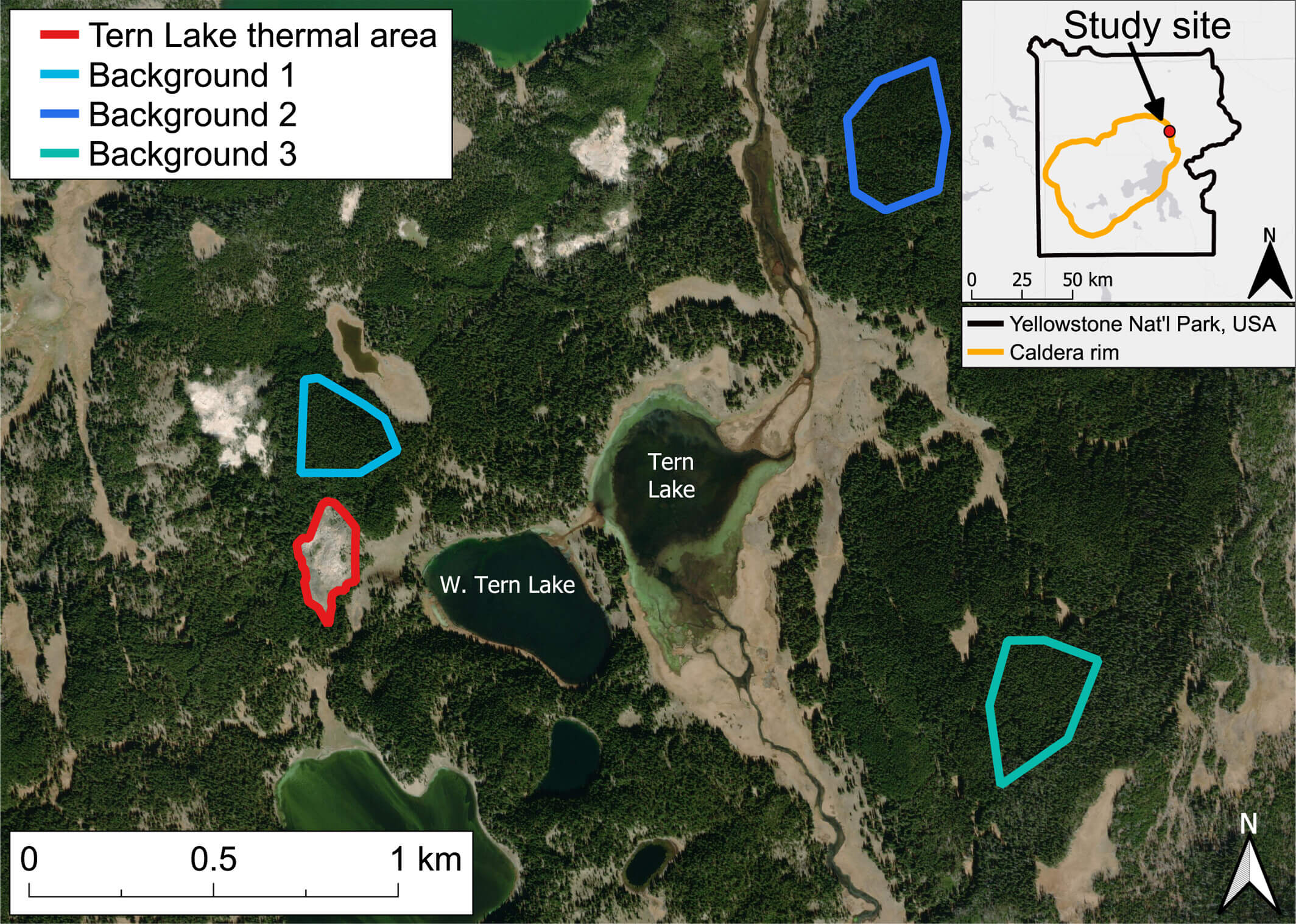

The phenomenon unfolded in the eastern Okavango Panhandle, a remote part of Botswana known for its rich biodiversity and complex waterways. This region, typically a haven for wildlife, suddenly became synonymous with death. Over 350 elephant carcasses were spotted during an aerial survey, a sight both perplexing and devastating. Initial speculations ranged from poaching to viral outbreaks, yet the actual cause remained elusive.

Recent studies, however, have shed light on this grim mystery, pointing towards an ecological imbalance that may have triggered the mass die-off. Researchers have unearthed evidence linking the deaths to cyanobacterial blooms in local watering holes—an unexpected toxicological twist in the tale. These blooms, also known as blue-green algae, are notorious for producing cyanotoxins, which, when ingested, can cause rapid and fatal neurological and liver damage. Dr. Emma Tebbs, one of the lead researchers from King’s College London, highlights that the cyanobacteria levels were unprecedented, with their occurrence peaking in the same timeframe as the elephant deaths.

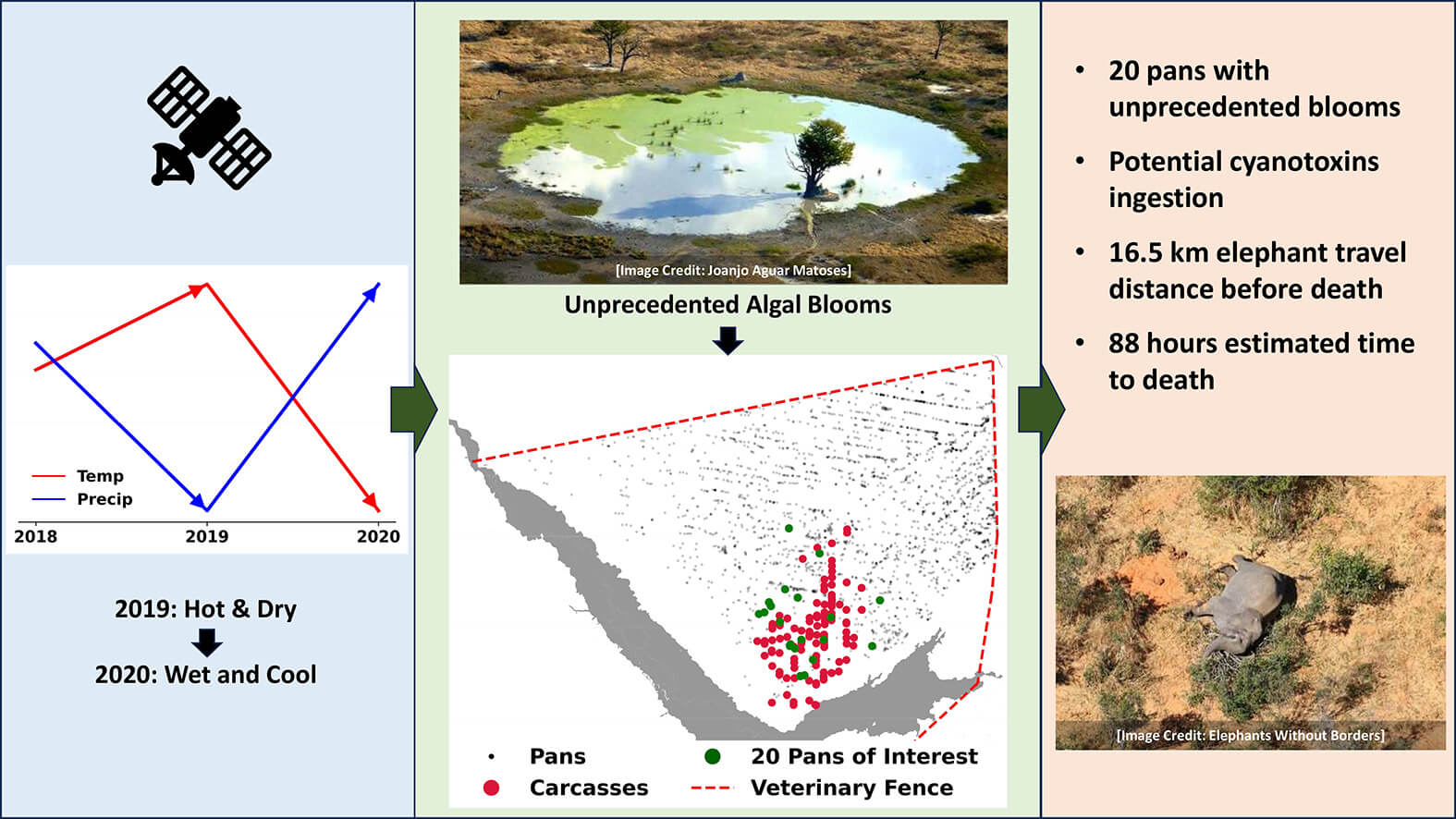

In 2020, Botswana experienced one of its wettest years following a drought period in 2019, a combination that appears to have driven the cyanobacterial explosion. Satellite imagery and spatial analysis conducted by the researchers revealed that certain waterholes, or pans, exhibited a dramatic rise in phytoplankton biomass. The Normalised Difference Chlorophyll Index (NDCI), a measure for estimating algal presence, indicated values exceeding thresholds previously considered safe for wildlife. The index showed a marked increase, with some pans registering NDCI levels above 0.3—suggesting a significant bloom event.

This ecological detective story unraveled further when the spatial distribution of the elephant carcasses was mapped alongside these bloom events. Elephants, known for their daily need to consume vast quantities of water, were found to have traveled significant distances, up to 16.5 kilometers, before succumbing to the toxins. The timeline of their deaths, estimated to occur within 88 hours after exposure, coincides eerily with the timing of the cyanobacterial blooms.

The implications of these findings extend beyond understanding the immediate cause of the elephant deaths. They underscore the broader environmental challenges and the intricate interdependencies within ecosystems, particularly in the face of climate variability. As Dr. Davide Lomeo, another key figure in the research, noted, “What we’ve seen in Botswana is a stark reminder of how delicate these natural systems are and how quickly shifts in climate can ripple through an ecosystem, with sometimes catastrophic consequences.”

This investigation also paves the way for more robust monitoring strategies using remote sensing technologies. By integrating satellite data with on-ground observations, researchers aim to develop early warning systems that could preempt such ecological crises. The hope is that these systems can be employed not only in Botswana but also in other regions where wildlife is similarly vulnerable.

As scientists continue to piece together the puzzle of the 2020 die-off, the study brings crucial attention to the impacts of environmental changes on wildlife. It highlights the urgent need for sustainable water management and habitat conservation strategies. Moreover, it raises questions about the resilience of megafauna in the face of rapid ecological shifts, pushing the boundaries of conservation biology to new heights.

Reference

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.177525