In a groundbreaking study that could reshape our understanding of Alzheimer’s disease, researchers have uncovered how a common respiratory bacterium, Chlamydia pneumoniae, may find its way into the brain, potentially contributing to the risk of this debilitating neurodegenerative disorder.

The study reveals that this bacterium can quickly invade the brain using the olfactory and trigeminal nerves — the very pathways that connect our sense of smell and touch directly to the brain.

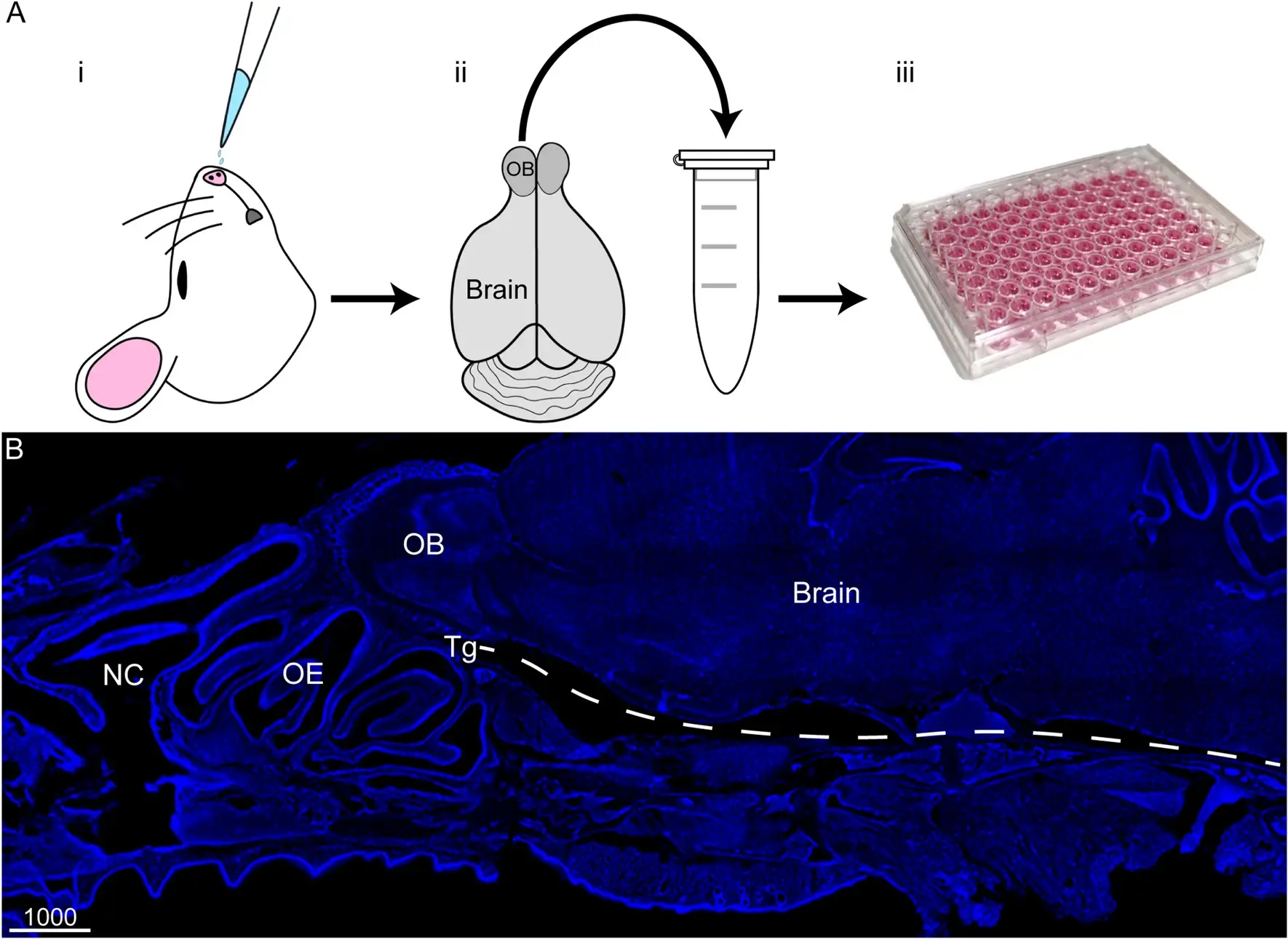

The research, conducted by a team led by scientists including Anu Chacko, Ali Delbaz, and Jenny A.K. Ekberg, utilized mice to observe how C. pneumoniae behaves after being introduced through the nasal passages. Within just 72 hours of intranasal inoculation, the bacterium was detected not only in the nasal cavity but also deep within the brain structures, particularly in regions like the olfactory bulb, which processes smell, and beyond.

This is not just a matter of simple infection; the implications are profound. Alzheimer’s disease, known for its characteristic amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques, showed a curious correlation with C. pneumoniae infections in these experiments. The researchers found that where the bacteria were present, there were also accumulations of Aβ, a protein whose abnormal buildup is a hallmark of Alzheimer’s. Interestingly, these accumulations were observed as early as 3 days post-infection, suggesting a rapid onset of potential neurodegenerative changes.

The study also explored how damage to the nasal lining could exacerbate this bacterial invasion. By using a methimazole injury model, which mimics damage to the nasal epithelium, the researchers noted a significant increase in bacterial load in the peripheral nerves and the olfactory bulb. However, this increase did not extend to the deeper parts of the brain, hinting at protective mechanisms that might prevent further bacterial spread once inside.

One of the key findings was the bacterium’s ability to infect and replicate within glial cells — the supportive cells of the nervous system, including astrocytes and microglia, which are known to be involved in Alzheimer’s pathology. This ability to form inclusion bodies within these cells could explain how C. pneumoniae survives and potentially causes long-term neuronal damage.

The genetic analysis conducted at 7 and 28 days post-infection further illuminated the connection between bacterial infection and Alzheimer’s. At 28 days, there was a noticeable downregulation of genes associated with protective responses to stress and protein folding, while there was an upregulation of genes linked to inflammation and cellular stress. Specifically, genes like Hspa1b, which helps in managing oxidative stress, were downregulated, and pathways involved in the unfolded protein response were significantly altered, potentially contributing to the neurodegenerative process.

Reference

Chacko, A., Delbaz, A., Walkden, H., Basu, S., Armitage, C. W., Eindorf, T., Trim, L. K., Miller, E., West, N. P., St John, J. A., Beagley, K. W., & Ekberg, J. A. (2022). Chlamydia pneumoniae can infect the central nervous system via the olfactory and trigeminal nerves and contributes to Alzheimer’s disease risk. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-06749-9