As heatwaves grow more intense and summers become drier, scientists are uncovering a hidden consequence of global warming that could affect millions: our ability to breathe. A new study warns that rising temperatures and drier air may be silently harming human airways, leading to increased inflammation and a higher risk of respiratory diseases.

For decades, researchers have known that extreme weather conditions can exacerbate asthma, allergies, and respiratory infections. But this new study, led by a team of scientists from Johns Hopkins University and other institutions, goes a step further, revealing how higher temperatures and lower humidity levels can directly impact the airways, even in people without pre-existing conditions.

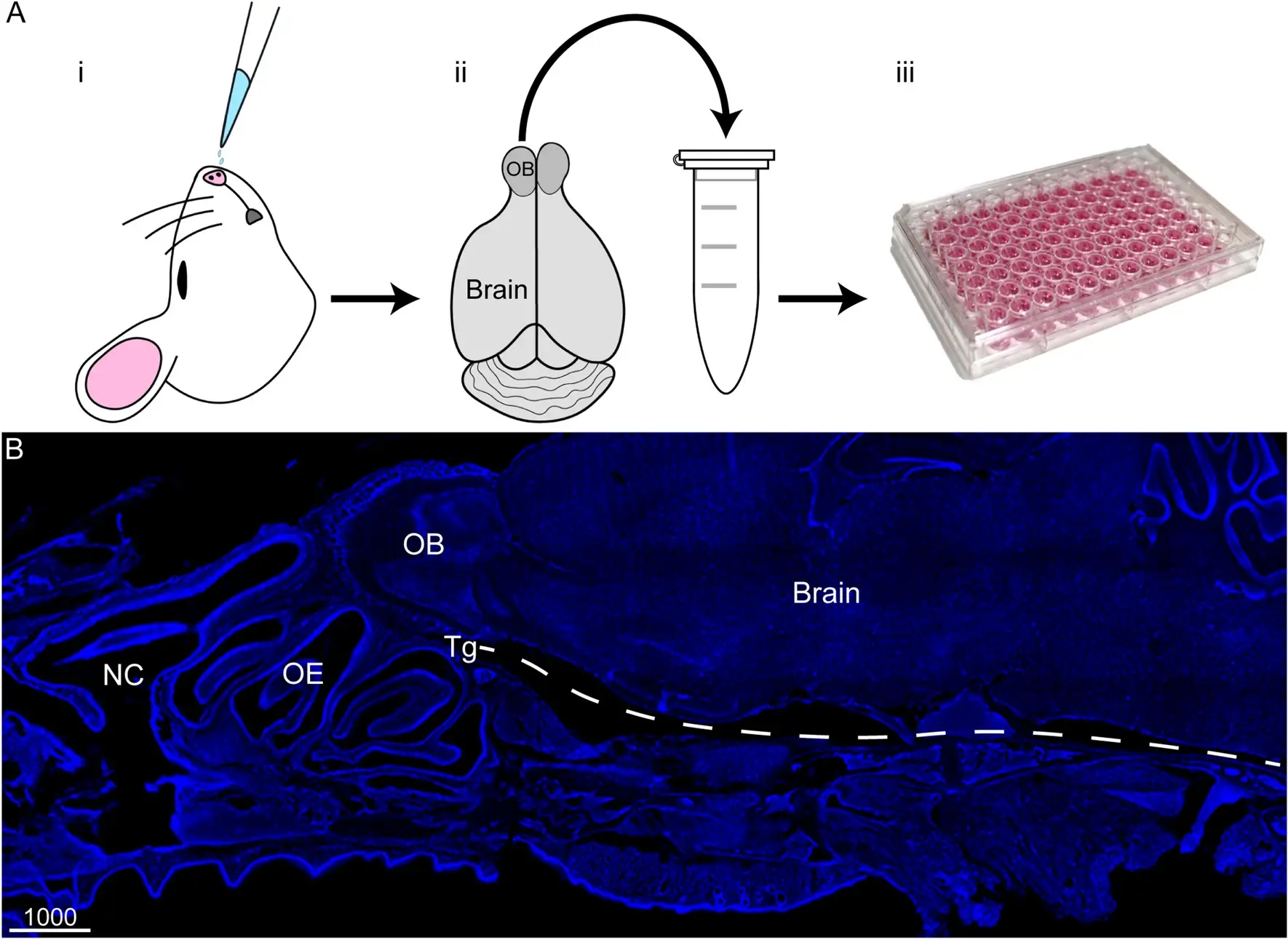

The research finds that as global temperatures rise, so does a measure known as vapor pressure deficit (VPD), which essentially describes how much moisture the air can hold. When VPD is high, the air pulls water from any available source—including the mucus that lines human airways. This drying effect was observed in a laboratory setting, where researchers exposed human tracheal-bronchial cells to air with varying humidity levels. At a relative humidity of just 30%—a level often found in heated indoor spaces during winter and increasingly in outdoor air due to climate change—the protective mucus layer in the airways thinned by 58%. Even at 60% humidity, which many would consider comfortable, the mucus layer shrank by 35%.

Why does this matter? The mucus in our airways serves as the first line of defense against harmful particles, bacteria, and viruses. When it thins out, it becomes less effective at trapping and removing these threats. Worse still, the study found that as airway cells dry out, they become compressed, triggering an inflammatory response. Key inflammatory markers—TNF-α, IL-33, and IL-6—spiked significantly in response to dehydration, signaling the body to react as though it were under attack.

The consequences of this process extend far beyond mere discomfort. The researchers also tested the effects of dry air on mice that were genetically predisposed to airway inflammation. After just 14 days of intermittent exposure to dry air, these mice showed signs of increased lung inflammation, with changes in their airway tissue resembling those seen in chronic respiratory diseases like asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

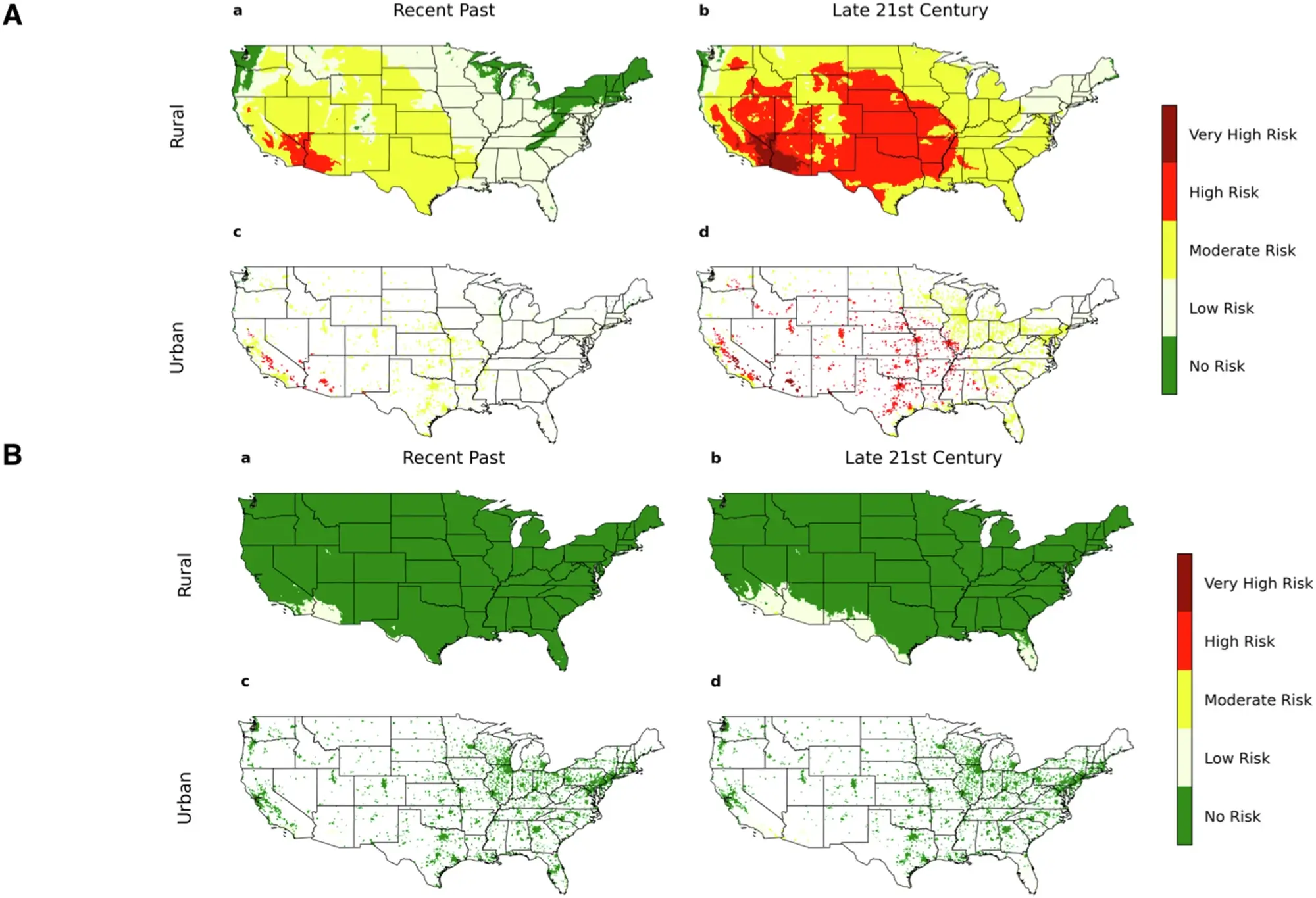

To understand the potential real-world impact, the scientists used climate models to predict how VPD levels will change across the United States by the end of the century. Their findings were alarming: in the past 40 years, only about 4% of the country’s land area experienced high or very high VPD during the summer. By 2060–2099, that number is expected to jump to over 40%, meaning vast portions of the population could be breathing in drier air year-round. Urban areas, already known for poor air quality, are expected to be hit particularly hard.

Kian Fan Chung, a co-author of the study and a researcher at Imperial College London, pointed out that this issue is compounded by modern lifestyle changes. “Chronic mouth breathing, which is becoming more common due to obesity, allergies, and other factors, exposes the airways to even drier conditions,” he explained. Nasal breathing naturally humidifies and warms the air before it reaches the lungs, but mouth breathing bypasses this process, putting even more stress on the airway lining.

Reference

Edwards, D. A., Edwards, A., Li, D., Wang, L., Chung, K. F., Bhatta, D., Bilstein, A., Hanes, J., Endirisinghe, I., Freeman, B. B., Gutay, M., & Button, B. (2025). Global warming risks dehydrating and inflaming human airways. Communications Earth & Environment, 6(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02161-z