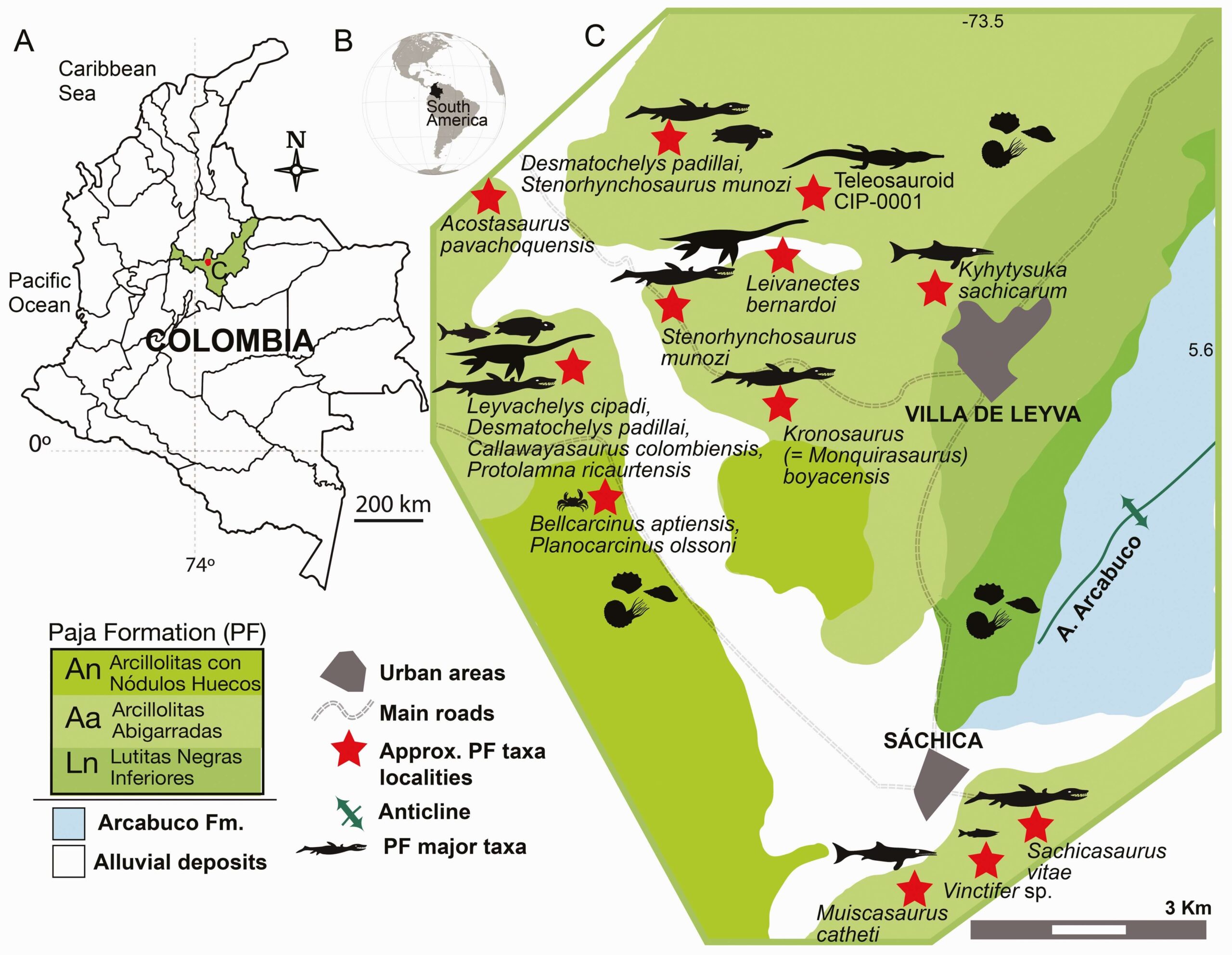

In the depths of Colombia’s Early Cretaceous past, a team of scientists has discovered evidence suggesting that ancient seas were home to formidable predators that might be described as the ultimate hunters of their time. This revelation comes from an extensive study of the Paja Formation, where researchers have pieced together an ecological puzzle of marine life millions of years ago.

The study, conducted by paleontologists Dirley Cortés and Hans C E Larsson, involved constructing a detailed food web for the marine ecosystem preserved in the Paja Formation, dating back to the Hauterivian through Aptian stages of the Early Cretaceous. What they found was astonishing: marine reptiles of this era could have occupied higher trophic levels than any predator in today’s oceans, earning them the name “hyper-apex predators.”

Cortés and Larsson’s work focused on the remains of numerous large-bodied, predatory marine reptiles alongside many ammonites, the dominant fossil group in this region. Ammonites, a type of extinct marine mollusk, numbered 112 species in the Paja Formation, indicating a biodiversity hotspot. However, it was the reptiles, including pliosaurs like Monquirasaurus boyacensis and Sachicasaurus vitae, both reaching lengths of about 10 meters, that stole the show in this ancient drama.

The researchers used quantitative ecological network modeling to understand the interactions between these species. They examined the body sizes, feeding morphologies, and inferred diets based on fossil evidence like tooth shapes and gut contents. This approach allowed them to map out who ate whom in this ancient aquatic world, revealing a network with 74 taxa and 977 trophic links, a linkage density of 13.2, and a connectance of 0.177.

What set this study apart was the recalibration of the Paja network against modern marine ecosystems, specifically those of the Caribbean. When comparing these ancient creatures to modern-day analogues, the researchers estimated that the largest predators in the Paja Formation could have been at trophic level 7, far above the typical apex predators in current marine environments like sharks or orcas, which usually max out around trophic level 5.6.

This finding isn’t just about big numbers; it’s about understanding the complexity and the energy flow in a prehistoric ocean. The Paja Formation’s ecosystem was rich with predators but notably lacked the small fish and invertebrates typically found at lower trophic levels in today’s marine systems. This absence might be due to taphonomic biases—where smaller, less durable organisms are less likely to fossilize—or it could suggest a unique ecological structure where large predators were more prevalent or dominant.

The study also sheds light on the Mesozoic Marine Revolution, a period where marine biodiversity underwent significant changes, leading to the complex ecosystems we see today. This revolution was marked by the evolution of new predatory strategies, like durophagy (the ability to crush hard-shelled prey), which might have initiated an arms race in marine fauna, driving evolutionary changes.

Moreover, the presence of such high trophic levels could indicate that these ancient seas supported an extraordinarily high level of primary productivity to sustain such a dense population of top predators. Imagine an ocean where the base of the food chain was so rich that it could feed giants, a scenario that might have no modern equivalent.

Reference

Cortés, D., & Larsson, H. C. (2024). Top of the food chains: An ecological network of the marine Paja Formation biota from the Early Cretaceous of Colombia reveals the highest trophic levels ever estimated. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 202(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zlad092