In a groundbreaking study, researchers have revealed that reducing exposure to toxic chemicals in plastics could prevent hundreds of thousands of deaths each year. The study, conducted by a team from various prestigious institutions, estimates that if exposure levels to certain common plastic additives had been lower in recent years, numerous lives could have been saved and cognitive development in children significantly improved.

The research focused on three notorious chemicals found in plastics: bisphenol A (BPA), di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP), and polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs). These are not just any additives; they are everywhere, from food packaging to electronics, influencing our daily lives in ways we might not even realize.

BPA, often used in the lining of food cans and plastic bottles, has been linked to serious health issues like heart disease and stroke. According to the study, in 2015 alone, BPA exposure was associated with 5.4 million cases of ischemic heart disease (IHD) and 346,000 cases of stroke across countries representing one-third of the world’s population. Imagine the implications if these numbers were extrapolated globally.

DEHP, another compound found in numerous household items, particularly those that need flexibility, like food packaging and medical tubing, was found to be linked with increased mortality rates among middle-aged individuals. The research suggests that in 2015, DEHP exposure might have contributed to approximately 164,000 deaths among people aged 55 to 64.

Then there’s PBDEs, used as flame retardants in everything from textiles to plastics, which don’t just stay in the product but can contaminate our environment, accumulating in household dust. The study points out that maternal exposure to PBDEs can detrimentally affect the cognitive development of children, leading to an alarming estimate of 11.7 million IQ points lost due to this exposure in 2015.

But here’s where the story takes a hopeful turn. The researchers, including Maureen Cropper from the University of Maryland and Philip Landrigan from the Boston College’s Global Observatory on Planetary Health, have shown that reducing these chemicals in plastics can lead to significant health benefits.

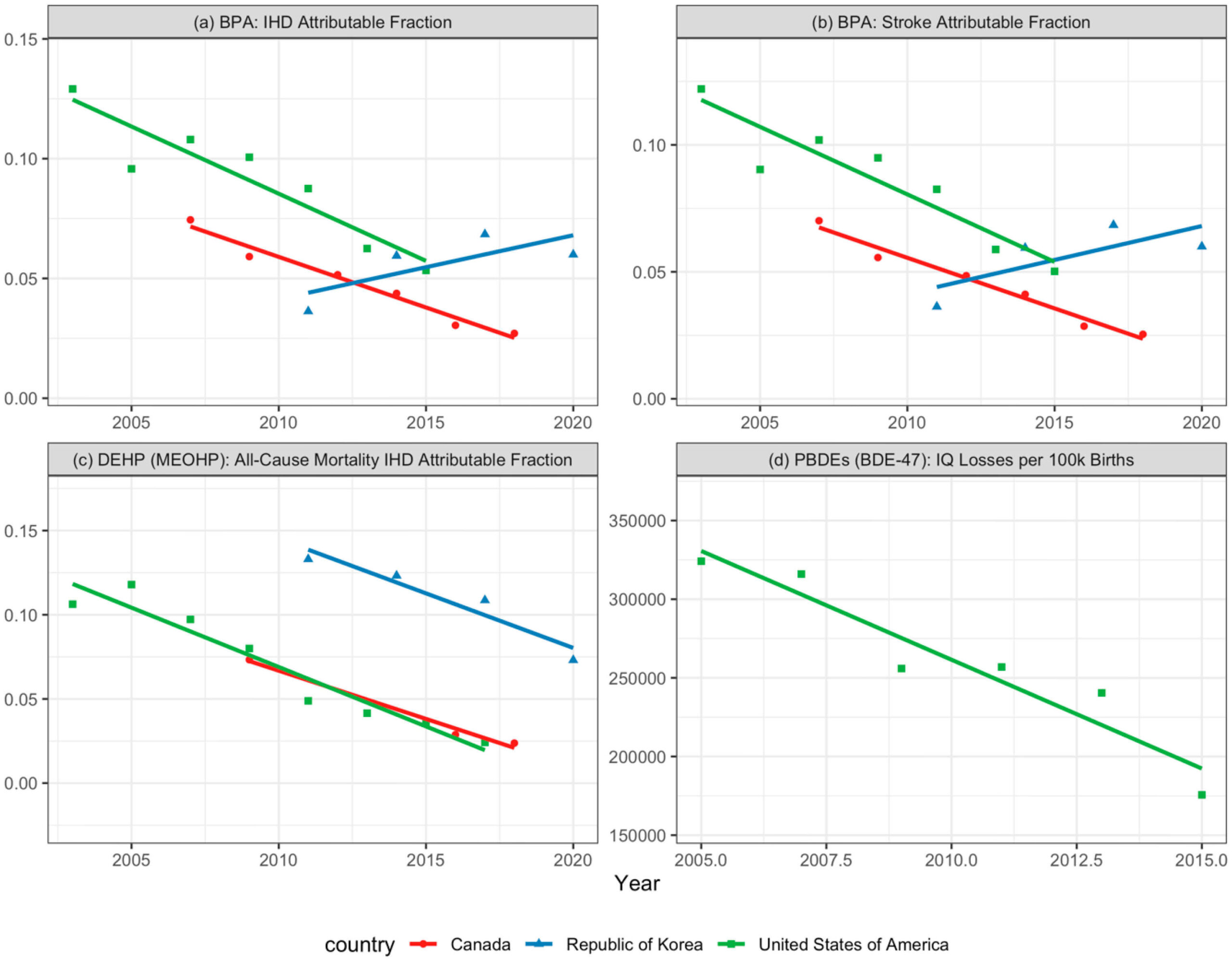

For instance, had the U.S. maintained 2015 exposure levels to BPA since 2003, the study suggests over 355,000 deaths could have been avoided due to reduced instances of heart disease and stroke. Similarly, maintaining 2015 levels of DEHP exposure since 2003 could have prevented 159,000 deaths. For PBDEs, keeping 2015 exposure levels would have saved over 42 million IQ points in children born from 2005 to 2015.

This research isn’t just about numbers; it’s about people. It’s about the grandmother who might not have to suffer from a stroke, the young mother whose child could thrive academically, or the middle-aged worker who could enjoy a longer, healthier life. The implications of these findings extend far beyond the lab. They touch on our daily choices, from the products we buy to the policies we support.

The economic impact is equally staggering. The study estimates the cost of these health impacts at $1.5 trillion in 2015 purchasing power parity (PPP) dollars, underlining the immense economic burden of inaction. This isn’t just a health issue; it’s an economic one, affecting healthcare costs, productivity, and quality of life.

The study advocates for a more proactive approach to chemical regulation, suggesting that current frameworks like the U.S. Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) fall short. It calls for a shift towards a system where chemicals are only allowed in products after they’ve been proven safe, rather than presuming safety until harm is demonstrated. This is a call to action for lawmakers, industries, and consumers alike.

Reference

Cropper, M., Dunlop, S., Hinshaw, H., Landrigan, P., Park, Y., & Symeonides, C. (2024). The benefits of removing toxic chemicals from plastics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121(52), e2412714121. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2412714121