For years, we’ve been told that high-density lipoprotein (HDL), often hailed as the “good cholesterol,” protects our hearts by sweeping away excess cholesterol from our blood vessels. But what if this guardian angel has a darker side?

Dedipya Yelamanchili and co have recently published a study that might just turn the narrative on its head. Their work, titled “HDL-free cholesterol influx into macrophages and transfer to LDL correlate with HDL-free cholesterol content,” suggests that HDL cholesterol might not always be the heart’s hero we thought it was.

The researchers started this study with a simple question: Can high HDL cholesterol levels sometimes be harmful rather than helpful? They gathered blood samples from ten healthy individuals, ensuring the cholesterol levels were within normal limits, and isolated HDL and low-density lipoprotein (LDL), commonly known as “bad cholesterol.” They then radiolabeled the HDL with a special type of cholesterol to trace its journey through the body’s cells and other lipoproteins.

What they found was both intriguing and concerning. The HDL cholesterol, rich in free cholesterol (FC), was not just taking cholesterol away from the arteries; it was also transferring it to LDL and into macrophages, a type of immune cell involved in the development of atherosclerosis, the buildup of plaques in our arteries that can lead to heart disease.

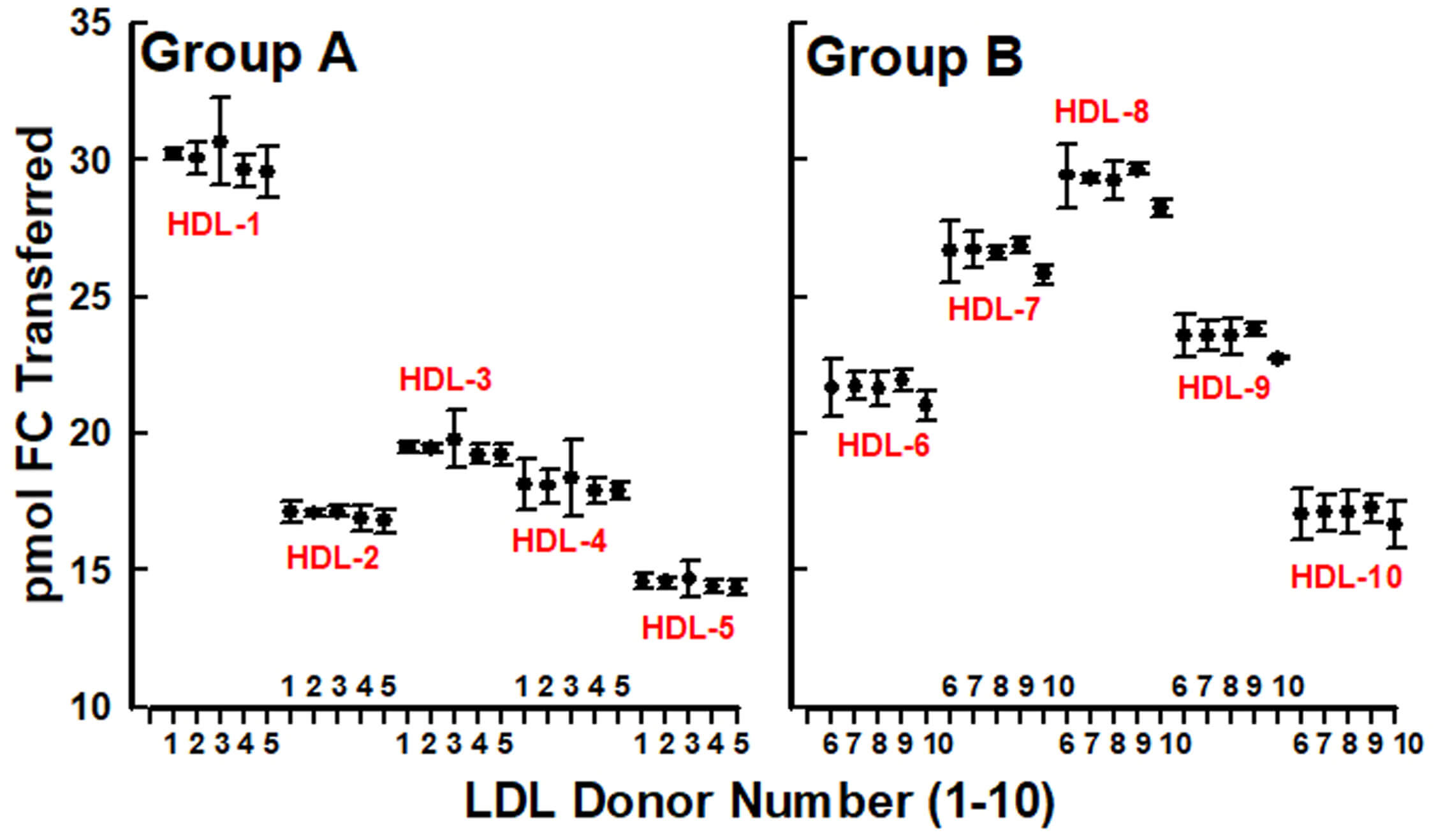

The study revealed a linear correlation between the amount of FC in HDL and how much of it was transferred to LDL. For instance, when HDL contained more FC, whether measured as moles per gram of HDL protein or as a percentage of HDL’s molecular composition, there was a corresponding increase in FC transfer to LDL. This transfer was not random; it was consistent across all LDL samples from different individuals, indicating that the key factor was the HDL’s FC content, not the LDL itself.

Even more startling was the discovery of how HDL interacted with macrophages. The team observed that macrophages absorbed more FC from HDL that had higher FC content. In their experiments, they noted that HDL with FC content ranging from 12.6% to 18.3% of its molecular makeup led to a significant influx of cholesterol into these cells. This could mean that in cases where HDL is overly rich in free cholesterol, it might contribute to the very plaque buildup it was supposed to prevent.

But why does this matter? Traditionally, high HDL levels have been associated with a lower risk of heart disease. Yet, this study suggests there’s a threshold beyond which HDL might not protect but rather contribute to heart disease. The researchers propose that the “bioavailability index” of HDL, a measure of how easily its cholesterol can be transferred, might be a new metric to watch for assessing heart disease risk.

Henry J. Pownall, one of the study’s authors, explains, “We’ve always looked at HDL as beneficial because of its role in removing cholesterol from the blood vessels. But our study shows that under certain conditions, especially when HDL carries a lot of free cholesterol, it might do the opposite, feeding cholesterol back into the system where it can cause harm.”

The implications of this research are far-reaching. If HDL can sometimes feed heart disease, then our approach to managing cholesterol might need an overhaul. It suggests that not all HDL is created equal, and perhaps we should focus more on the quality and function of HDL rather than just its quantity. This could lead to new diagnostic tools or treatments that target HDL’s composition or function, rather than simply boosting its levels.

Reference

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlr.2024.100707.