In a recent outbreak in South Dakota, researchers from the University of Pittsburgh discovered that the H5N1 avian influenza virus might have adapted to domestic cats, raising concerns about its potential to bridge the species gap to mammals. This was reported following the deaths of several outdoor cats in the area, which exhibited both respiratory and neurological symptoms.

The H5N1 virus, particularly the clade 2.3.4.4.b, has been notorious since its first detection in China in 1996, and it has been found spreading across a wide spectrum of bird and mammal species. Traditionally associated with respiratory issues, this strain has shown increasing neurological impacts in mammals such as sea lions and red foxes, and now, domestic cats. The study titled “Marked Neurotropism and Potential Adaptation of H5N1 Clade 2.3.4.4.b Virus in Naturally Infected Domestic Cats,” published in Emerging Microbes & Infections, highlights these developments.

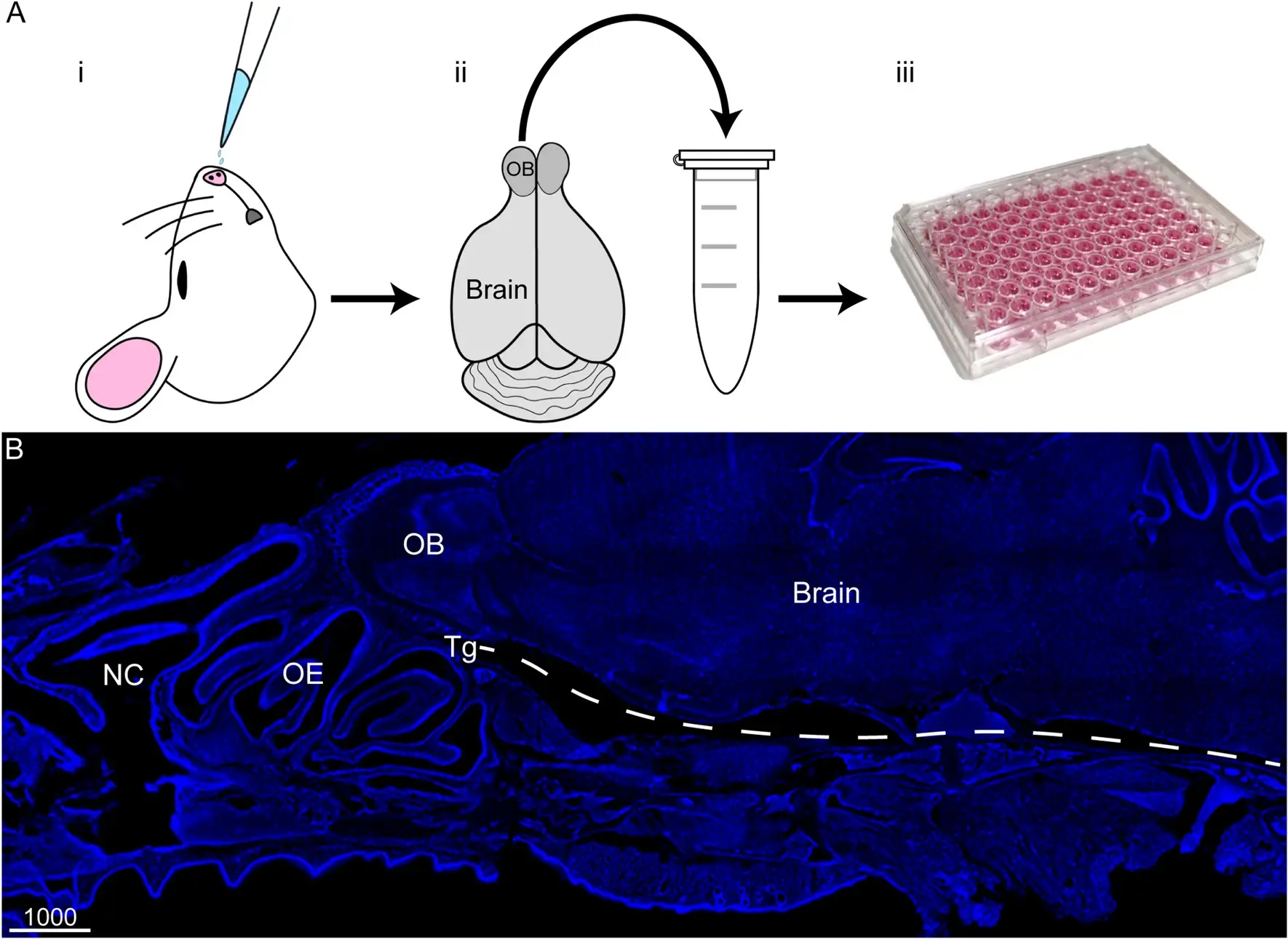

In April 2024, ten cats in South Dakota were found dead, showing severe respiratory and neurological signs. Necropsies conducted at the North Dakota Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory confirmed the presence of the H5N1 virus in the brain and lungs. Genetic analysis suggested a close relationship with strains previously found in local dairy cattle, hinting at possible interspecies transmission.

The cats’ tissues revealed significant lesions in the brain, including neuronal necrosis and inflammation, with the viral load in the brain surpassing that in respiratory tissues. The virus’s ability to affect neurological tissues so severely suggests a marked neurotropism—an adaptation potentially facilitating transmission across species.

The study found widespread co-expression of sialic acid receptors in cats’ lung and brain tissues, which are compatible with both bird and human influenza viruses. This receptor compatibility might allow the virus to jump between species, including potentially to humans.

While there are no current reports of human infections stemming directly from these cat cases, the potential for cats to act as mixing vessels for viral mutations poses significant public health concerns. This could pave the way for new, more dangerous influenza strains capable of infecting humans. The situation underscores the need for heightened surveillance of H5N1 in both domestic and wild animals to prevent animal-to-human transmission.

These findings parallel earlier incidents in Texas, where H5N1 was linked to dead cats and birds on cattle farms, suggesting a broader, concerning trend. The key takeaway from this research is the urgent need for comprehensive monitoring of H5N1 to understand its spread and mitigate risks of a potential new pandemic.

The study by Shubhada K. Chothe and colleagues calls for enhanced vigilance to assess and mitigate the risks associated with this virus, emphasizing the necessity to stay one step ahead in pandemic prevention.

Related Posts

Reference

Chothe, S. K., Srinivas, S., Misra, S., Nallipogu, N. C., Gilbride, E., LaBella, L., … Kuchipudi, S. V. (2024). Marked Neurotropism and Potential Adaptation of H5N1 Clade 2.3.4.4.b Virus in Naturally Infected Domestic Cats. Emerging Microbes & Infections. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2024.2440498